What is Emergent Community Design?

Part two of my four-part series on emergent community design

Welcome to Part II of my series on emergent community design:

Part I: How Communities Emerge

Part II: What is Emergent Community Design? (this post)

Part III: How to Bring a Community to Life

Part IV: How to Design a Community Container (coming soon!)

Part V: The Seven Principles of Emergent Community Design (coming soon!)

Note: This thesis is, itself, emerging. What was originally a three-part series is now a four-part series. As this thesis unfolds I invite you all to add your reflections, feedback, and questions in the comments and replies.

In Part I, we explored the basic concepts of emergence in nature and how it applies to communities. If you haven’t already, I’d recommend reading that post first. In Part II we’ll begin to apply emergence to the work of creating and facilitating communities.

Part II will cover:

✔️ Defining “emergent community design”

✔️ Intentional vs unintentional communities

✔️ The universal river of connection

✔️ The three rules of community emergence

✔️ The community butterfly effect

Defining “emergent community design”

Let’s kick off Part II with a definition of “Emergent Community Design”.

This definition will serve as the foundation for the rest of this series.

Emergent community design:

An intuitive, experiment-driven approach to designing communities that recognizes communities as complex, living systems.

Usually, a community is described as something we “build”, “architect”, or “engineer”. Rooted in these terms is the belief that building community is a linear, step-by-step process. “If we just follow the instructions, we’ll have a community!”

Emergent community design challenges this assumption. It’s rooted in the belief that we don’t build communities. We build containers where community has a chance to emerge. And to some extent, what emerges will always be out of our control.

In emergent community design, we form hypotheses and run experiments until a community emerges. Once it emerges, we continue to shape through experimentation and observation. It’s an iterative process that requires fluidity and adaptability.

Once a community begins to emerge, you don’t have to do anything. Like a plant, it will just continue to emerge on its own. Your job is to care for it, guide it when needed, and help it reach its full expression.

Intentional vs unintentional communities

It’s important to note that the emergent community design methodology is specifically focused on intentional communities, which I’m defining as a community that someone intends to create.

In unintentional communities, no one is designing them in any particular way. They just emerged from the social environment. Riots, mosh pits, friend groups, and neighborhoods can all be unintentional communities, at least until someone decides to take the lead.

There must be leadership for an intentional community to exist.

Leadership doesn’t have to be formal. Even in decentralized communities with no formal leadership like holocracies, open-source projects, or DAOs (decentralized autonomous organizations), leadership will emerge organically.

Unintentional communities are the closest thing to the type of bottom-up emergence we see in nature. When the environment is right, the complex entity (like flocks of birds, schools of fish, and colonies of ants), will just emerge, no leadership required.

For humans to form intentional communities, a leader must take action. Someone must make a conscious decision to gather and/or shape the community.

The universal river of connection

“The things that cause us to feel pain [are] evolutionary recognized as threats to our survival. The existence of social pain is a sign that evolution has treated social connection like a necessity, not a luxury.”

- Matthew Lieberman, Social Cognitive Neuroscience Lab Director at UCLA

Here’s how I see it…

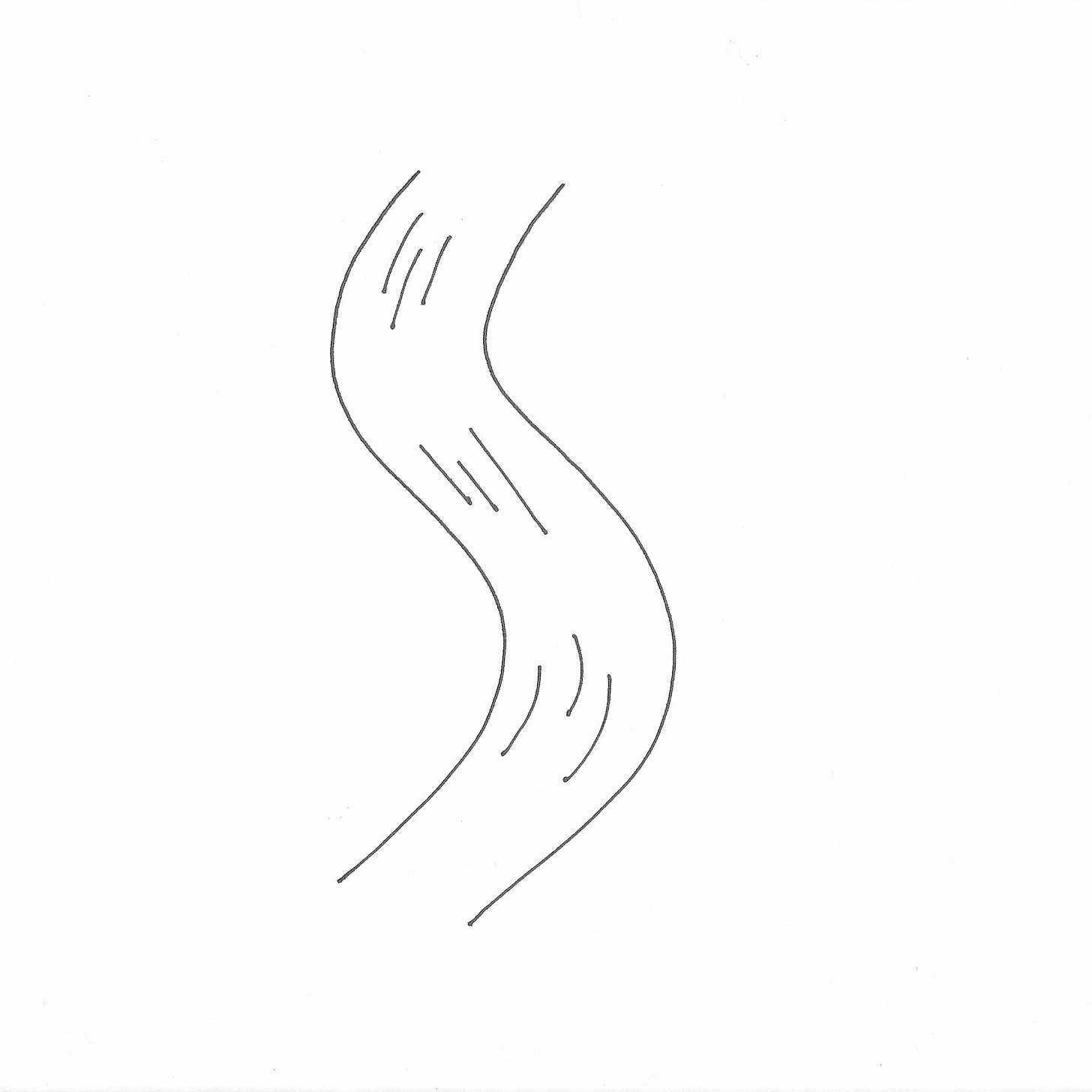

Flowing through all of humanity is a giant river of connective energy. The river is always in motion. We are always seeking connection.

When you start a community, you’re hoping that the river of connection will flow into the container you construct.

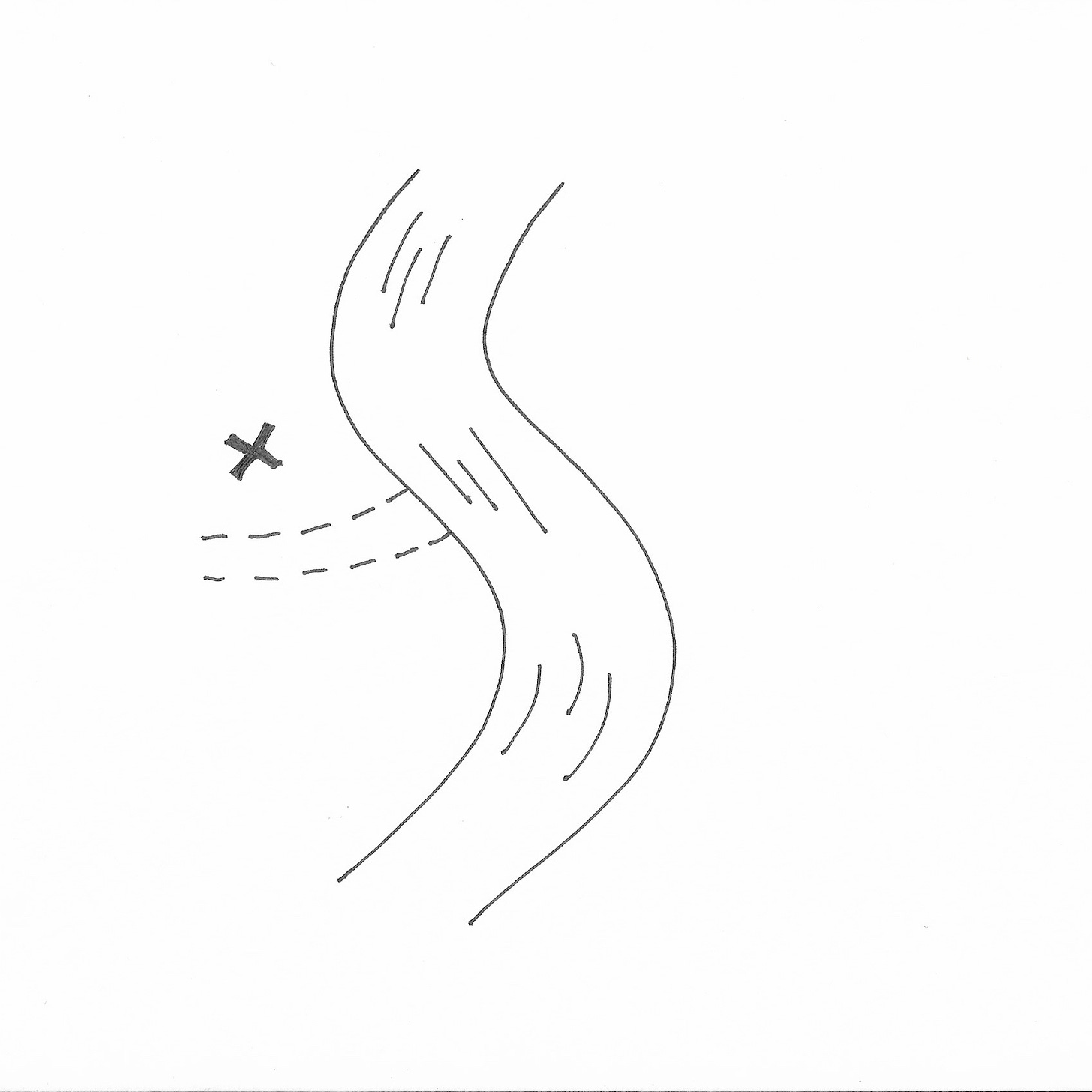

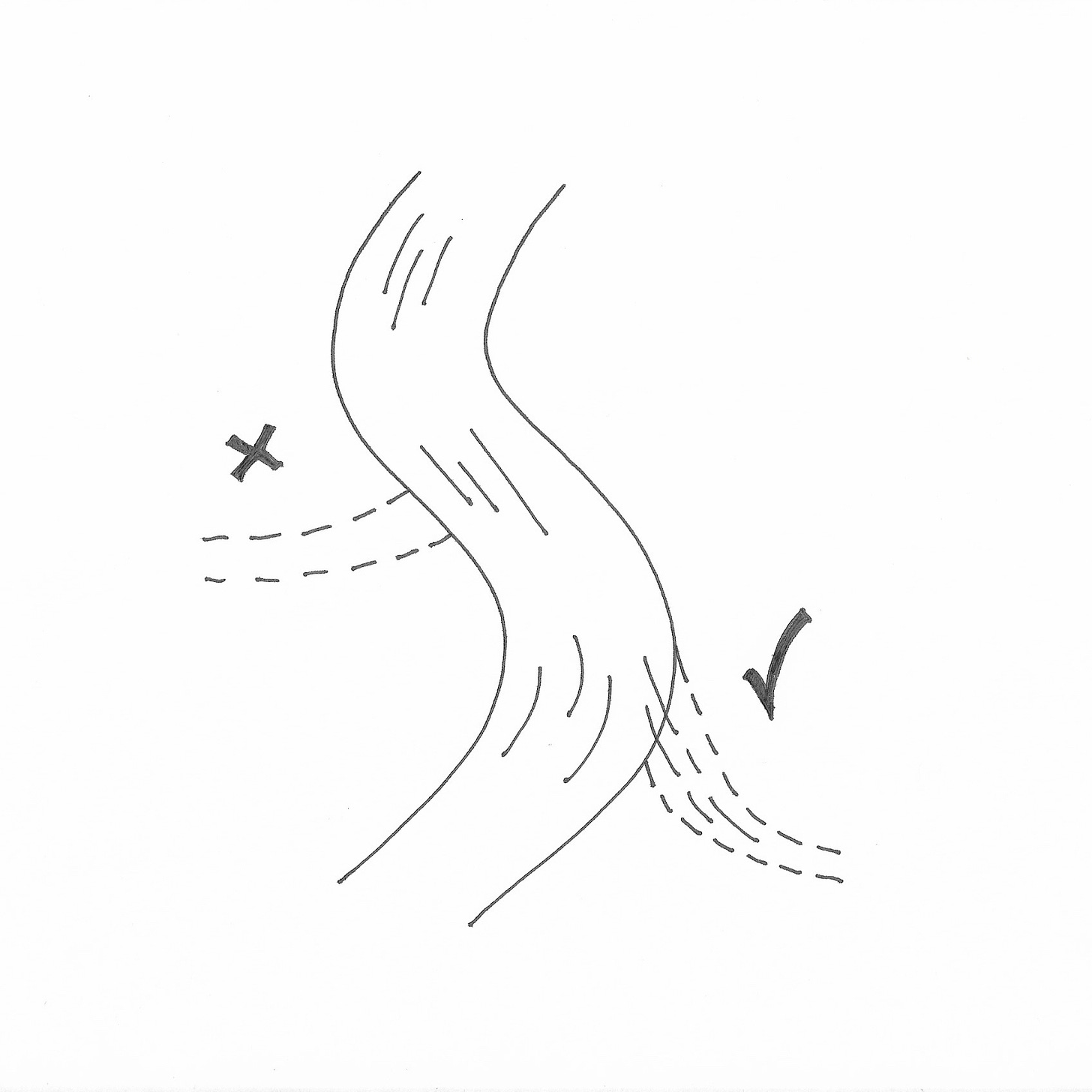

When you position the community container wrong, the river refuses to flow into it. There’s too much friction. You’re trying to change the direction of the river’s flow too much. You’ll notice it’s taking a great deal of effort to get any engagement going.

When you get the community design right, in line with where the river naturally wants to go, connection flows into it with ease. It feels alive and joyful. You’ll realize that you don’t have to do much to get engagement going, the community is emerging on its own.

Once the river is flowing through your community, you get to decide how hands-on or hands-off you want to be with shaping it. Do you want to let the river carve its own path? Do you want to guide the river in any specific direction? We’ll talk more about these decisions in Part III.

The direction of the river’s flow is constantly changing. Other communities will form, in flow with the new direction of the river, and pull the connective energy out of your container into theirs. If your community doesn’t adapt to the river, it will run dry.

The rules of community emergence

So what has to be true for the river of connection to flow into the community space you’ve created?

To explore this question, let’s fly back to our old friend, the starling.

In Part I, we learned that for a flock of starlings to come together, each bird must follow three rules:

Fly toward the center

Don’t collide

Match speed and direction with your nearest neighbors

This got me wondering, what are the rules that must be followed for a human community to form?

I see three:

Sufficient motivation

Fulfillment of promise

Consistent opportunities for interaction

—

There must be sufficient motivation to overcome the friction of participation

Motivation can be intrinsic (pure yearning), extrinsic (rewards), or a combination of both. But keep in mind, extrinsic rewards have diminishing returns. Once the extrinsic reward’s value fades, so will their motivation. The most sustainable communities are ones that are fueled by pure intrinsic motivation.

It’s not enough for members to be motivated. The motivation has to be greater than the friction of participation.

Friction comes in many forms: money, time, travel, clunky software, cognitive load, introversion, risk of leaving an existing community, competition for attention, fear of exclusion.

It’s not necessarily about reducing the friction. People have literally climbed Mt. Everest to find community. It’s often about finding the people who yearn so deeply for this interaction, that they’ll overcome the friction required for participation.

Then again, sometimes it is about reducing the friction (eg. choose a venue that’s more convenient, or an online platform where people are already spending time).

Participation must fulfill the promise of the community

All participation is not created equal. Members’ contributions have to generate value for other members. I call this the Community Activation Point.

Think about an event where everyone is just handing out business cards instead of connecting. Or an online community where everyone just promotes their own stuff. Yes, there’s participation, but it’s creating little to no value.

If your community promises love and support, then members have to contribute their love and support. If it promises answers to their questions, then members have to contribute answers to their questions. If your community promises dope memes… you get the point.

There also has to be enough members in the room for the community to serve its purpose. Easy for a six-person discussion group. More difficult for a large conference or online forum.

There must be consistent opportunities to participate

For the community to persist, members need to be able to come back and participate again and again.

Some communities only need one big event a year and that’s enough.

Others require more frequent opportunities to connect.

Online communities are generally available 24/7.

Whatever the cadence, if members can’t come back and contribute over time, the community will fade.

The community butterfly effect

“The flapping of the wings of a butterfly can be felt on the other side of the world."

- Chinese Proverb

Great so the three rules have been met, and the river of connection is flowing into your community. What happens next?

The community will begin to unfold, usually in unexpected ways.

Leadership controls the structure of the container and the behavior they model, but they can only influence what will ultimately emerge.

Countless factors influence what emerges in the container that a leader creates: Words, colors, sounds, smells, histories, biases, social norms of the time, time of day, time of year, tone of voice… everything plays a part.

With so many factors at play, what will emerge is unpredictable. Often, something seemingly insignificant will have cascading effects on the community culture over time.

Say, for example, you’re in a community for accountants.

One day a member makes a joke about “counting your chickens before they've hatched.” It was a bit corny but community loved it.

Next week someone references the chicken joke in a hilarious callback. Everyone laughs again.

Another callback follows. Then another. It’s now a running joke.

Fast forward three years and the community has changed its logo to a chicken. Downvotes have been replaced with rotten eggs. Everyone wears chicken hats to the annual accounting conference.

I call this the “community butterfly effect.”

This is how inside jokes form. It’s also how communities form cultural norms, social structures, roles, rules, rituals, and all of the other emergent attributes we discussed in Part I.

What emerges might be serious or silly, beautiful or ugly, inclusive or exclusionary, peaceful or violent, organized or chaotic.

The work of community leadership is to observe what’s emerging and regularly run experiments to guide the community in the direction of its vision.

How exactly? That’s where we’ll pick up in Part III.

Lets review…

That’s all for Part II! This essay focused on the foundations of emergent community design. Here’s what we covered:

✔️ Defining “emergent community design”

✔️ Intentional vs unintentional communities

✔️ The universal flow of connection

✔️ The three rules of community emergence

✔️ The community butterfly effect

Using what we covered today as the foundation, we’ll dive into the design process you can follow to bring a community to life in Part III. See you there. (bring your chicken hat)

My gratitude to the thoughtful humans who took the time to read an early draft of this post and offer their feedback and reflections: Jami Diaz, Sharath Kuruganty, Matt Yao, Brian Helfman, Amy Jo Kim, Michael Daigler, and Taraqur Rahman.

Your turn

Does this resonate or am I whackadoodle?

Do the three rules ring true? What’s missing?

Does the definition make sense? What would you change?

How do you see emergence playing out in your community today?

What’s your favorite chicken-themed joke?

What questions are you still holding as we move into Part III?

Drop a comment or reply. I’d love to hear your reflections.

I love this! It’s such a great way to frame it. One of the things emergence brings up is lifespan. And how death is natural and not all things are meant to last forever and the question of how we hospice a community when it’s no longer of service. Do we just let it fizzle, do we something formal and to end and honor it…?