Community and Wealth

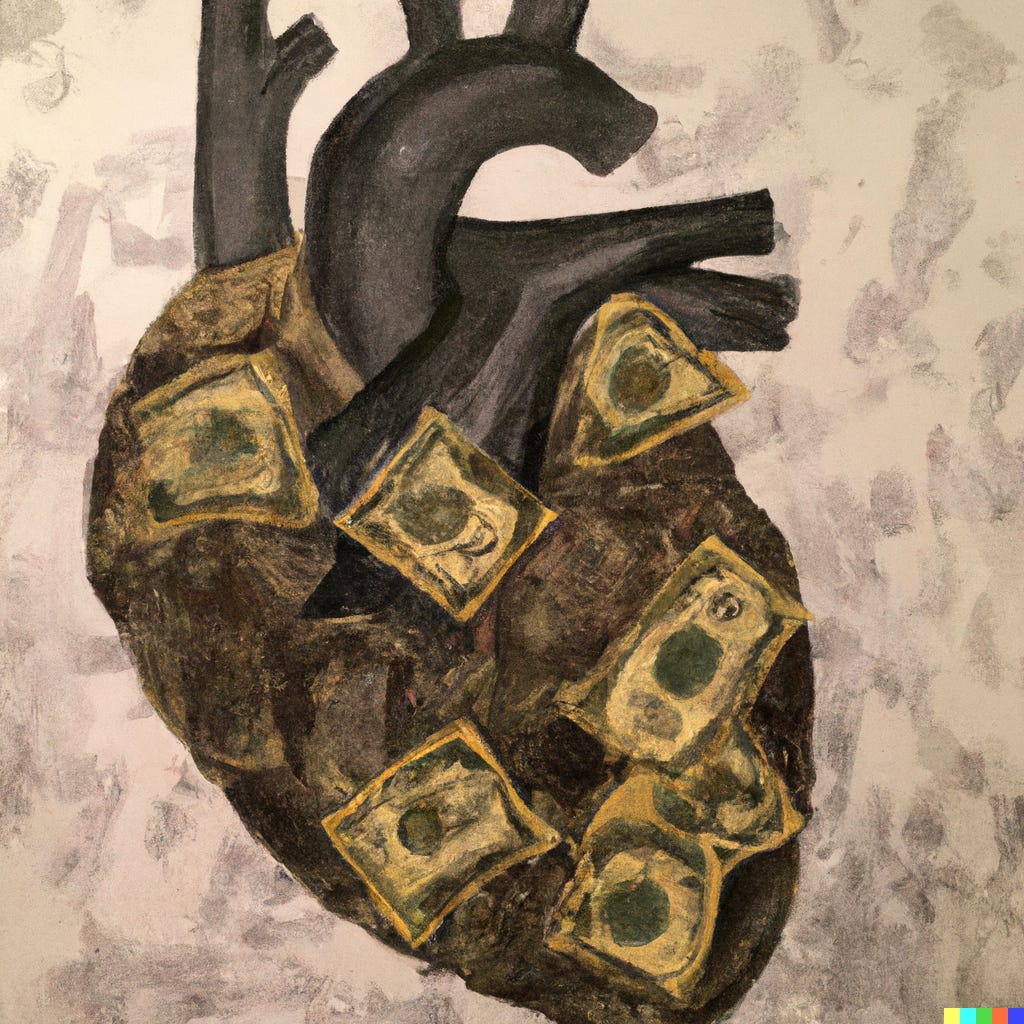

Making money, building belonging, and the community builder's dilemma

I’m reading a book called How to Get Rich, by Felix Dennis.

The title is terrible. When I pulled it out on a plane a couple weeks ago, I rushed to put it in the backseat pocket before my neighbors could see it. The book itself, however, is really good.

Dennis was a publisher, poet, and philanthropist who founded Maxim Magazine and pioneered a lot of the first computer magazines in England. He passed away in 2014.

I’m enjoying the book not because I want to become super rich (I don’t… though I do have relative wealth goals). I’m enjoying it because Dennis gives you a candid take on what being rich means, the mentality one must have to become rich, and the sacrifices you need to make. In essence, it’s helping me understand wealth and the wealthy. He’s also a hilarious writer, which helps.

Wealth is a topic that many people find to be taboo, and most will tiptoe around for fear of coming across as greedy. In the community space, you rarely hear it discussed at all, at least not in positive terms.

A couple weeks ago, while on stage at CMX Summit, I wondered to myself how many hands would go up in the crowd if I asked the audience of community builders, “How many of you want to be wealthy?” Probably none.

It wouldn’t be that no one in the crowd was seeking wealth, but because in the community community, wealth isn’t celebrated. Fear of judgment would keep hands in laps.

But there’s an opportunity to bring more nuance to how we talk about wealth in the world of community. It’s something we should talk about more.

These can be stormy waters, so grab your life jacket, fill it with equal parts cash and empathy, and let’s dive in…

The Business:Belonging Dilemma

Throughout my career I’ve straddled the wall between community and entrepreneurship.

My first job out of college was a community manager for a startup that would become SeatGeek. When I was offered the job I remember thinking, “holy shit, I can’t believe someone will actually pay me to do this!” Up to that point, I built and wrote about community because I found it fun.

So began my career in community. I’d spend the next 13 years working in this space as a community lead on various teams, as a consultant, and eventually launching CMX to establish community as a professional industry. My goal was to make community a legitimate, highly-valued, integral part of business.

In the back of my head the question always loomed, “What if we succeed? What if every business in the world starts investing in community? Will community become overly commercialized? Should we be mixing community and profit?”

And so in lies the dilemma that many community builders hold in their minds, consciously or not.

We do this work because we love people. We love connecting people with each other. We fight loneliness, create friendships, support people who are suffering, help people grow and change, and care that our work has a positive impact on the world. I haven’t yet met a community professional who doesn’t value these things highly.

AND, we work for businesses. Often venture-backed or public companies whose goal is to increase shareholder value. We want to get paid for our work. We want our work to be valued. We want the community industry to grow. We work hard to quantify the impact that community has on the bottom line. Some time ago, when asked about the business value of relationships, Gary Vaynerchuk quipped, “What is the ROI of your mother?” Every day the community industry inches closer to being able to answer that question.

If that feels icky, that’s normal. Humans view the world in what behavioral economist Dan Ariely calls, “market norms and social norms”. Market norms are transactional, supply and demand, buying and selling, equal exchange of value. Social norms are interpersonal, like doing a favor for a friend, holding the door open, or volunteering. When the two get mixed, it can feel wrong. Like offering a friend money to help you move. Or when a CEO tells their staff how much he cares about them while announcing layoffs. Money and relationships are often best left in their own lanes.

This tension is what drew me to choose The Business of Belonging as the title for my book. The two words felt like they were on different ends of a spectrum. We all hold the cognitive dissonance of business and belonging in our psyche every day we show up to do the difficult work of bringing people together for a business.

Businesses can seek profit thoughtfully. They may have strong values, and a clear mission, they may even be a B-corp or donate a percentage of all profits, but at the end of the day, they must make money.

Even non-profits must account for their bottom line. A non-profit founder recently lamented to me how difficult it’s been for their staff to understand that for all the purist goals they have as an organization, they still have to do the work that will get them grants. “Without grant money, the impact stops”, they said plainly.

Sometimes money will cause a business to make decisions that feel very counter to purist views of community. People get laid off. Pay gets cut. Community spaces get shut down. But these sacrifices are made to ensure that the company can survive.

No company, no community.

Stating your Intentions

The business:belonging dilemma shows up in the daily interactions community builders have with their members and causes them to be dishonest.

We welcome new members and say, “We care about this community, you’re our #1 priority!” because, to us, it’s true. But it’s also an idealistic view that isn’t fully based in reality. A more full truth would continue, “...as long as it’s profitable. If not, we’ll likely have to cut this community.”

But you can’t say that, right? Well no, not like that. But there’s room to bring more truth into how we communicate with our communities.

A more honest approach would be to say, “We care about you AND we hope that one day you’ll buy our product. As a for-profit business, we want to be honest about our ultimate goal to grow revenue. We want to take a human-first approach to selling by helping you, connecting you with your peers, and earning your trust. Once in a while, we’re going to ask you if you’re interested in buying our product. It’s okay to say no… we’ll still help you because we take a long view on earning customers.”

That feels honest. Customers will have more trust in a company that’s upfront with them.

The dilemma shows up in conversations with our teams and bosses as well.

Community professionals know all too well the uphill battle of proving the value of community engagement. Experienced community professionals learned over the years that to be successful they need to start with the business goal, then design community engagement around that goal. You’re doomed if you start with engagement and then try to connect it to business value later.

For every other business function, it’s assumed that they are part of the profit-making machine: sales, marketing, operations… even HR and Design. We know, intuitively, they’re working toward a profit goal. But for community, we try to convince ourselves that we’re special, doing something higher, something better, something more moral. I’ve seen many ride that high horse straight to irrelevance.

Our paychecks come from the same well as everyone else’s. Our success is measured by the same ultimate results. It’s money.

The Financialization of Community

I recently joined the Friends with Benefits (FWB) community which ran me roughly $8,000 to buy the 75 tokens I needed to become a member. FWB is a community built on the blockchain, and the tokens are tradeable, so their value changes with the market.

Those tokens are now worth less than $1,000. Such is the risk you’re expected to take when your membership is tied to a tradable asset. My participation in the community required financial risk and speculation, whether I wanted it to or not.

Crypto gave us a window into this interplay of community and money. In its most recent iteration, it made money and membership inseparable.

Community became the primary selling point for Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs), Non-fungible Tokens (NFTs), and Decentralized Finance (De-fi). Community roadmaps became the new pitch decks.

It’s a weird space where on one hand, it’s felt like the fullest expression of “community-driven business”, preaching values of distributed wealth and community-based governance. Why shouldn’t community members benefit from the financial upside of their participation?

In FWB, they’d often talk about “Squad Wealth”, or the idea that if a community-driven business is successful, it will create wealth for all of its contributors. Austin Robey made a strong case for how DAOS could solve the biggest challenge facing co-ops: funding.

On the other hand, it showed us what the fullest expression of financialized community looks like. A world where every membership, every contribution, every event, has a dollar value attached. It made community feel more cold, transactional, and hype-driven. It also showed us how community can be weaponized, using the trust generated by the promise of connection and belonging to lure people, and their money, into scams.

I’m in the camp that believes capitalism is good, and that community is critical for keeping capitalism in check. Social norms are a check on market norms because they beg the question, “what is the human cost of this profit?”

Web3 has shown me that financializing a community removes its power to be a check by making social and market norms indecipherable. It became impossible to know people's true motivations. Are they helping me because they care about me as a person? Or because they wanted to earn tokens? Are we making a decision for the collective good of our members or for the value of the token?

In Predictably Irrational, Ariely explains that when money is introduced to an exchange, the financial incentive replaces our social motivations.1 He shared a study where one group of lawyers were asked to do unpaid pro-bono work for people who couldn't afford their fee and another group was asked to paid work, but for a fee much lower than their usual rate. The lawyers asked to do the work for free accepted the cases at a higher rate than the lawyers who were asked to do the work on the cheap. Why? Because the first group was still working within social norms. As soon as market norms were introduced, the lawyers started thinking in terms of money, not people.

In Web3, it doesn’t matter how communal your intentions are, if there’s money involved then you are working with market norms. (I have a lot of new thoughts on the state of web3, and it’s not all negative, but I’ll save that for another newsletter).

Here’s a big question…is it really that different in Web2?

We may not be tracking community actions with tokens, but we’re still working to assign dollar values to community engagement. Our community members feel like they’re interacting within social norms when in reality there are market norms at play. At least in Web3 members are aware of the financial dynamics. They’re present in Web2 as well. We just don’t talk to members about it.

Are community and capitalism at odds?

Let’s zoom out. The truth is everything has a financial element to it in capitalism. There isn’t a single social construct that doesn’t need funding in order to be sustainable, from friends and families to churches to hobby groups…they all need money. Since that money isn’t coming from a central government, it has to come from somewhere.

I asked on Twitter the other day, Are community and capitalism at odds?”. The answers varied widely and people used a lot of words I had to look up like “corporatism” and “cronyism”.

Some people fell into the camp of “capitalism is bad” and nothing we do within the bounds of our capitalist system is going to be good for humanity. Others were die-hard capitalists who believe deeply that it’s the optimal system for collective wellbeing. Most were somewhere in the middle.

George Siosi Samuels reminded me of one of the original definitions of capitalism in the view of Adam Smith:

“It is liberty, in Smith’s view, that is at the heart of capitalism, and at the heart of liberty lies commitment to the good of humankind. Considering Smith’s position reminds us of a long-standing, but increasingly endangered, American moral sensibility: liberty and the economic freedom it entails serve the common good.”2

Capitalism, in Smith’s view, is good to the extent that it serves our collective well-being. Of course, that’s easy to say in practice, but who’s included in the collective? In an unjust society, it’s always going to be the underrepresented and underprivileged who suffer for the benefit of those in power. Common good, without true equality, isn’t very good.

But let’s say we can reach that idealistic future of true equality of opportunity. Capitalism gives people the opportunity to change their lives for the better, to leave communities that aren’t serving them and join new communities where they can thrive. It incentivizes us to keep building and creating value for each other.

I think we’re very lucky to find ourselves in a stage of capitalism where community is beneficial to the bottom line. This wasn’t the case in the early days of the industrial revolution where people were just numbers with no power.

A pointed example of the clash of community and capitalism happened just a couple weeks ago. The design platform Figma was acquired by Adobe for $20 billion. My initial reaction was, “That’s amazing news for the community industry!” Figma, as far as I understand it, is a stellar example of a community-driven business. Their community-first approach has been documented. Community wasn’t an afterthought for them. The team preached and practiced community since day one. It was core to their approach in everything from product to marketing. So when I saw the news, I was thrilled. $20 billion! One of the largest acquisitions EVER. What great validation of the power of community-driven business.

But the sentiment from many in the community industry was less positive (see comments here).

Some had good reasons for concern. I think Anil Dash said it best on Twitter when he joked:

That concern seems totally reasonable. Consolidation and untenable scale are areas where we have to ask the question, “Is this in the best interest of the common good?” The tech industry should adjust if it seems like we’re actually hurting ourselves. Of course, the government can also step in if consolidation crosses the line into monopolization. These are important social and policy checks on capitalism.

But for many others, their disdain with the Figma acquisition felt more personal. There seemed to be anger that people made money. An allergic reaction to sudden increases in wealth. They didn’t see it as a success story of a community-driven business. They saw it as selling their community out.

As someone who has sold a community, I feel qualified to say that an acquisition does not mean selling out your community. In the case of CMX getting acquired by Bevy, that decision actually saved the community. Just a few months before the acquisition, my team and I sat down and had a real conversation about sunsetting CMX Summit, our annual conference. The event was hugely impactful for the community and the industry, but it was the lowest return on investment of all of our revenue channels because of how much time it took. Because of the acquisition, CMX Summit lived on. Three years later it’s still going and brought together over 6,000 community builders just last month.

As a community founder, nothing could make me happier than seeing the community live on after I’ve left, and remain financially sustainable.

I’m happy for Figma. I’m happy for the founders who stuck to community and for the early community team who (I hope) earned wealth from the acquisition. I’m not a designer so it doesn’t really affect me, but I understand the concern from their community members that Adobe will ruin Figma. It certainly can, but it doesn’t have to. Based on what their CEO is saying, I’m optimistic it won’t.

Microsoft didn’t ruin Github. Despite massive concerns at the time, the community overall has been happy with the product improvements since the acquisition. Stripe didn’t ruin IndieHackers. Outreach didn’t ruin Saleshacker. Bevy didn’t ruin CMX. In all of these cases, getting acquired didn’t ruin communities, it enhanced them.

We are at our best when we figure out ways for community and capital to drive each other.

I Wish You Wealth

How to Get Rich showed me that I don’t actually want to become rich, at least not to the level that Dennis talks about. The sacrifices he claims I’d have to make just aren’t worth it to me. This is his list:

“[Should you find yourself unable to measure up to even one of these initial demands (and I mean just one), then my suggestion is that you close this book and give it to a friend:

If you are unwilling to fail, sometimes publicly, and even catastrophically, you stand very little chance of ever getting rich.

If you care what your neighbors think.

If you cannot bear the thought of causing worry to your family, spouse or lover while you plow a lonely, dangerous road rather than taking the safe option of a regular job, you will never get rich.

If you have artistic inclinations and fear that the search for wealth will coarsen such tallents or degrade them, you will never get rich (because your fear, in this instance, is well justified)

If you are not prepared to work longer hours than almost anyone you know, despite the jibes of colleagues and friends.

If you cannot convince yourself that you are ‘good enough’ to be rich.

If you cannot treat your quest to get rich as a game.

If you cannot face up to your fear of failure.]”

At this stage in my life, I care too much about being able to do the creative work I want to do in the way I want to do it (like writing this newsletter). And while I’m still working on “the courage to be disliked”, I still care what my peers think.

Don’t get me wrong, I still want wealth to the extent that I can live my life the way I want to. Epictetus defined wealth as consisting of, “not in having great possessions, but in having few wants.” While I work on removing “wants” from my life as a path to wealth, I also know that some wants will only be removed with a certain amount of money. Money won’t solve all your problems, but it will solve some.

I wish wealth for all community builders. I know how hard this work is. I know the struggle of having a huge vision for your community, but lacking the funds to get there. Whether you’re a community founder or building community within a company, you deserve capital to do your work well, and you deserve the opportunity to generate wealth for yourself and your family.

My hope is that we can welcome conversations around wealth and profit in the community world, without jumping to the conclusion that it’s bad for our communities, bad for the world, or too taboo to discuss amongst compassionate company.

Use community as a check, but let’s not make it an impenetrable wall.

—

Thank you to Nadia Asparouhova, Alison Malfesi, Greg Isenberg, and Angie Coleman for their thoughtful feedback and edits on this article.

Predictably Irrational: https://danariely.com/books/#book-predictably-irrational

Adam Smith on Capitalism and the Common Good: https://www.econlib.org/library/Columns/y2020/Matsoncommongood.html

My current thesis that I've been writing about: communities are too focused on the inputs (engagement) rather than the outcomes. Many communities don't actually solve real problems and therefore people get tired pretty quickly.

It's like having a local town hall meeting and talking about all the things that need to happen. Sure it's great to gather and talk about things, but it won't last or won't matter if action is not taken.

So, inputs (conversations, attendance, etc) are important, but what matters are outputs. The action. The problems solved. The tangible growth that people have experienced. These are the products, so to speak. Nothing wrong with making money through them, imhro.

Focusing on outcomes is what is needed, but with a finely balanced community mindset. It's the balance is what I think is lacking.

A little bit less conversation, and a bit more action. 🎶 (Inspired by Elvis Presley, hah)

I'm excited by this though, I think it shows there's still much room to grow and talk about when it comes to community + business/money.

Great piece, David! It’s been a joy to silently follow your journey over the years. I resonate a lot with your thoughts. Think this is a nuanced piece to bridge both community building and wealth, two topics I’ve personally been thinking about as well.

I feel like you where you mentioned you want wealth but not at the expense of your creative pursuits and other things in your life. Thanks for writing. 🙌